When we talk about risk mangement within PETER, mostly we related it with EMI. However, for each of us, risks are everywhere and can be related to anything around us. This blog gives an example of how to apply risk management in our lives.

I. Introduction

Have you ever watched the movie “Life of Pi”? This is a story revolving around an Indian man named “Pi” Patel, telling about his life story, and how at 16 he survives a shipwreck and is adrift in the Pacific Ocean on a lifeboat with a Bengal tiger. Coincidentally, in the real world, there is such a kind of people who always experience similar stories like Pi, but more mentally rather than physically. Luckily but also unluckily, I’m one of them. To let you know how risky a PhD student’s life may look like and how a PhD student can survive from these risks, in this blog, the real life of a PhD student will be introduced and analyzed. The remainder of this Blog is organized as follows. Section II shows the issues (or hazards, potential contributors to risks) that this PhD student faced. In Section III, the detailed process of how this PhD student applies his research (risk management) to solve these issues is described. Finally, the PhD student’s one year’s life is concluded and future work is proposed. Besides, suggestions for other PhD students to keep alive and going forward are also provided in Section VI (for reference).

II. Issues / Hazards

More than one year ago, I walked into the land of Belgium as a PhD student. At the beginning, everything is fresh but interesting and exciting, e.g., new colleagues, historical buildings with different architectural styles, as well as unfamiliar Dutch/French languages. The feeling was just like young Pi first got onboard the ship, ambitious and hopeful.

However, as the quotation of Forrest Gump’s mom states: “life is like a box of chocolates, you never know what you’re gonna get” [1]. After the initial freshness, issues came one by one. Firstly, daily life issues. There are so many rules that are different from my home country, which are quite annoying to me. For example, I understand all the garbage need to be classified for recycling, but why so meticulous (Fig. 1)? I have a blue “PMD” garbage bag to hold plastic, metal and drink carton items, but why I also have to prepare a white bag for plastic film and a separate container for paper (not those technical ones that I’m working on)? Not to mention the black daily waste bags. Similar situations to the energy (electricity and gas). Many energy suppliers told me they’re the most cost-effective and provided me with lots of data and analysis to prove that. Unfortunately, since I’ve already got so many analysis and calculations in my own research, I really have no interests to do another complicated research in the “energy” area. But all in all, such daily life issues took me much time and vigor.

Fig. 1: Daily life issues – garbage classification

Secondly, language issues (Fig. 2 [2]). Since I’m living in the Dutch area, most people’s first language is Dutch rather than English. Many times, when I was about to pay at the counter, the cashier spoke to me in very polite Dutch, followed by my same polite but embarrassing question “could we speak English?” I always ask myself: do I look like I can speak Dutch? So far, the only explanation is that I look so smart that they think this guy must know Dutch. Thank them and I’ll try my best.

Fig. 2: Language issues

This situation also extends to my work (that’s why I don’t want to attribute it into daily life issues). During my working days in company, at first, I was happy to join my colleagues’ lunch communication. However, when more Dutch speaking colleagues joined, the official language for lunch moved to Dutch and from then on, I kept either eating or smiling. Such language difference reduced my communications with people around me, which more or less made me feel lonely.

Last and the most important issues are research-related issues. Since I started my research in a new area, I needed to learn new knowledge and skills. At the beginning, when I was full of ambition and motivation, this was not a problem. As I thought, knowledge is always there, I just need to grasp and apply it. But when I really started, I found things were different. The knowledge does exist, but not simply stay “there”, waiting for you to grasp. Instead, it is the question of “where”, and sometimes even “everywhere”! A good analogy is that previously, the research target was like a still rabbit standing there, shown by the supervisor/teacher, and what I need to do was aim and shoot the rabbit with my gun of knowledge. However, now doing research requires me to find and shoot a fast-moving rabbit in the vast forest by myself! Such a big cognitive gap led me to an ineffective way and let me down for quite a bit of time. Especially, due to the Covid-19 lockdown period, the reduction of effective communications with supervisors and colleagues made this situation even worse (Fig. 3, [3]). Each time I saw my colleagues working on papers or making progress, I felt both admirable and depressed. Moreover, since I’m not a person who can totally separate work and life, the feeling of depression followed me all the time, e.g., before sleeping, the moment of waking up, hanging out. It influenced my mood and sometimes prevented me from concentrating on my job.

Fig. 3: Issues during research

III. Risk Management Process

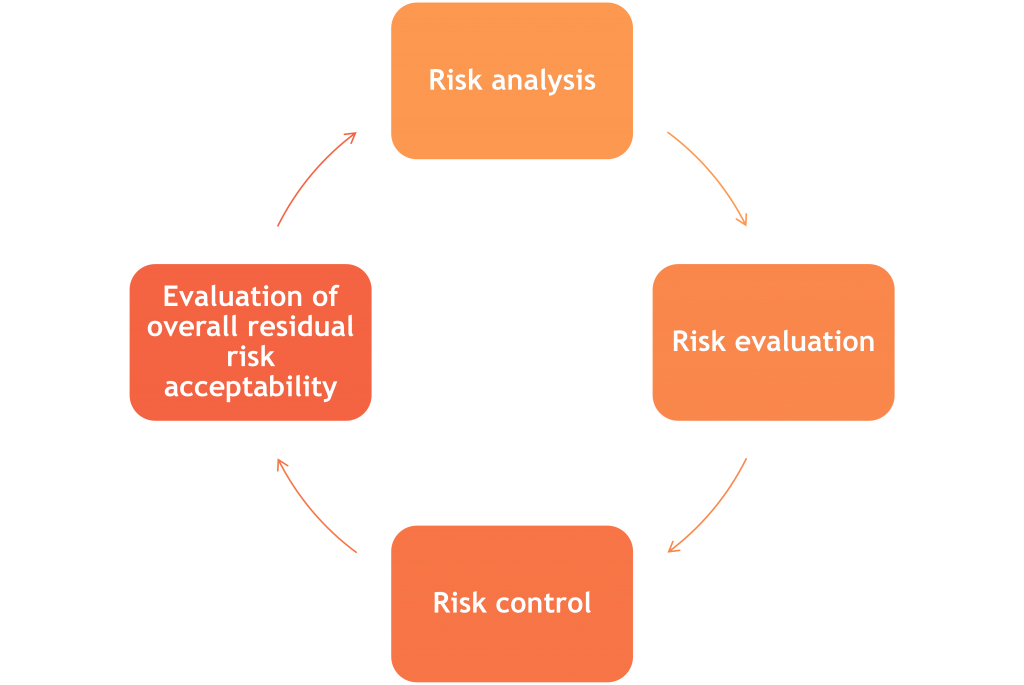

As humans, one difference between us and most animals is that we have emotions. On the one hand, this uniqueness enables us to generate various of negative sentiments, like being annoyed by garbage issues, feeling embarrassing or lonely with language issues and being bothered by depression. On the other hand, the ability of feeling different emotions motivates us to get out of negative ones and tend to positive ones. In other words, we always try to be away from disadvantages (remove or reduce risks) and move to advantages (seek safety). Coincidentally and fortunately, managing risks is exactly one important part of my research. Thus, by dealing with aforementioned issues with my professional knowledge (Fig. 4, starting from risk analysis), I could have a good chance to practice my research in real life.

Fig. 4: Simplified risk management process

A. Risk Analysis

From the professional perspective, to manage the risks, the first step is “risk analysis”. Since my situation is not complicated, this “risk analysis” can be simplified to “hazards identification” and “estimation of each hazardous situation”. As already identified in Section II, the hazards range from daily life, language to research. Each hazardous situation is also easy to be estimated with common sense plus some brainstorms. The daily life issues related risks (hereafter referred to R1) are close to my daily life, which means they are very likely to occur. R1 can be taking up too much of my time, thus delay my work and worsen my moods. For the language issues, the possible risks (hereafter referred to R2) are causing embarrassing situations. However, considering the special period of lockdown, there won’t be many occasions with lots of Dutch speaking people. Therefore, R2 won’t appear frequently. When looking at risks that due to the research issues (hereafter referred to R3), it can be seen that many risks can occur. For example, I may suffer from depression each day, postpone getting the degree or even lose a wonderful job opportunity in the future. For their occurrences, when I become more familiar with the way that research should go, R3 won’t appear frequently, either.

B. Risk Evaluation

This step is to determine whether risk reduction is required for each risk. For R1, since they are very likely to occur and cause tolerable but annoying results, R1 need to be removed or reduced. Since R2 are not very serious now and they can gradually vanish due to my learning Dutch and being familiar with more colleagues, thus R2 can simply be ignored. For R3, though they won’t show up very frequently, once occur, disastrous consequences can be caused. Thus, R3 definitely need mitigation measures.

C. Risk Control

Risk control is to mitigate those risks as decided in risk evaluation. As described in Section III.B, only R1 and R3 need mitigation measures. For R1, I listed all the detailed issues that need me to put efforts on and then focus on solving them within a certain time. Note that there are two kinds of measures for R1. One kind is permanent measures, meaning that you just need to execute them once and relevant risks will be removed or reduced to acceptable levels permanently, e.g., choosing the appropriate energy supplier. The other kind is periodic measures. For these measures, their risks will occur periodically, but as long as you set some effective rules, the only remaining thing is to simply follow these rules, e.g., classify the garbage.

For R3, things become more complicated. The reason is that to reduce R3, many factors have to be taken into consideration. For instance, the frequency of communication with supervisors should not be too low (because low frequency communications always give the impression that one is too inactive and thus solve problems). Besides, interactions with other PhD students around are important since they can alleviate your depression (because sometimes you may find they also undergo similar stress). Considering all of them, with the proposal and help of my supervisors, I took my secondment in KU Leuven Bruges Campus. By doing this secondment, I greatly increased my communication frequency with my supervisors which brought me lots of extreme new views, e.g., supervisors will kindly help you instead of simply commanding you to do this or that. You can argue with them, rather than just follow their words. Meanwhile, this secondment also provided me more interactions with other PhD students, which let me understand that they also have difficulties like mine. Encountering such problems is quite normal to everyone and this doesn’t demonstrate that I’m stupid. Moreover, I also enjoyed the sunrise and sunset during my daily return journey between Bruges and Kortrijk… to summarize, this secondment benefited me so much that it excited me again!

D. Evaluation of overall Residual Risk Acceptability

As you may already guess from my above description, all the measures I’ve taken so far are quite effective. At this moment, I’ve almost finished writing my very first scientific paper, feeling much happier than before. Comparing to several months ago when I have to worry about what I should show to my supervisors, now I care more about which paper can be useful to my research and how to enjoy my life after one day’s work. Although I still have shortcomings that need to be fixed and improved, I trust myself more than before.

Table 1: Risk Management Summary

| Hazards | Corresponding Risks | Probability | Severity | Needed Mitigation Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily life issues | R1 | Frequent | Limited | Centralized one-time processing |

| Language issues | R2 | Remote | Negligible | N.A. |

| Research issues | R3 | Occasional | Very severe | Interact with supervisors and colleagues, separate work and life… |

IV. Conclusions and Future Work

In this blog, the life of a PhD student is shown with relevant risks identified and managed (Table I). By using a risk management process, all the risks are effectively removed or at least reduced to acceptable levels. Based on such experience, several suggestions that can keep PhD students away from risks are provided. First, be patient to daily life trifles and solve them asap. Though they look insignificant, they can steal your time and vigor if you leave them there. Second, sometimes if you don’t understand others’ words, just ask or keep smiling. Always remember, if you don’t feel embarrassed, then it’s others who will feel that. Finally, always trust yourself and keep interaction with people around. You’ll be surprised by how much they’re willing and able to help you. Of course, you should always be ready to give back.

The future work will include more experience, e.g., repairing a car which breaks down halfway, fighting against writing a journal paper. For sure, more useful advices will be given out accordingly.

As mentioned in Section I, I’m unlucky to suffer from such difficulties as a PhD student. However, I’m also lucky to learn from these difficulties, become stronger and more powerful. PhD students are not as easy as many people imagined, but if you take the proposed suggestions, you have a higher chance to keep alive and make it.

References

[1] Forrest Gump (Film). Robert Zemeckis (Director). 1994. Paramount.[2] “Overcoming the language barrier”, https://mini-ielts.com/115/reading/overcoming-the-language-barrier

[3] “COVID-19 and mental health: Construction is not immune”, https://canada.constructconnect.com/joc/news/ohs/2020/05/covid-19-and-mental-health-construction-is-not-immune

About the Author: Zhao Chen

Zhao Chen is an Early Stage Researcher, affiliated with the Healthcare R&D department at Barco NV. As ESR12, he will focus on EMI-Resilient Medical Display systems for Surgical- and Diagnostic Imaging and Modality Applications. His ultimate objectives are to complete and optimize the existing rule-based Design-for-EMC process with/for IEC 60601-1-2:2014, to specify test-cases that are based on different types and use cases of displays and display systems for medical application and to apply and assess the novel EM-risk analysis methodology on the test-cases.

Zhao Chen is an Early Stage Researcher, affiliated with the Healthcare R&D department at Barco NV. As ESR12, he will focus on EMI-Resilient Medical Display systems for Surgical- and Diagnostic Imaging and Modality Applications. His ultimate objectives are to complete and optimize the existing rule-based Design-for-EMC process with/for IEC 60601-1-2:2014, to specify test-cases that are based on different types and use cases of displays and display systems for medical application and to apply and assess the novel EM-risk analysis methodology on the test-cases.